Food Science and Technology, Nutrition, Food Safety, Dietary Supplement & Health related blog - Kshitij Shrestha

Friday, August 28, 2020

Risk Assessment of Aflatoxins from JECFA

Thursday, August 13, 2020

EFSA Risk Assessment of Aflatoxins in food

Abstract

EFSA was asked to deliver a scientific opinion on the risks to public health related to the presence of aflatoxins in food. The risk assessment was confined to aflatoxin B1 (AFB 1), AFB 2, AFG 1, AFG 2 and AFM 1. More than 200,000 analytical results on the occurrence of aflatoxins were used in the evaluation. Grains and grain‐based products made the largest contribution to the mean chronic dietary exposure to AFB 1 in all age classes, while ‘liquid milk’ and ‘fermented milk products’ were the main contributors to the AFM 1 mean exposure. Aflatoxins are genotoxic and AFB 1 can cause hepatocellular carcinomas (HCC s) in humans. The CONTAM Panel selected a benchmark dose lower confidence limit (BMDL ) for a benchmark response of 10% of 0.4 μg/kg body weight (bw) per day for the incidence of HCC in male rats following AFB 1 exposure to be used in a margin of exposure (MOE ) approach. The calculation of a BMDL from the human data was not appropriate; instead, the cancer potencies estimated by the Joint FAO /WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives in 2016 were used. For AFM 1, a potency factor of 0.1 relative to AFB 1 was used. For AFG 1, AFB 2 and AFG 2, the in vivo data are not sufficient to derive potency factors and equal potency to AFB 1 was assumed as in previous assessments. MOE values for AFB 1 exposure ranged from 5,000 to 29 and for AFM 1 from 100,000 to 508. The calculated MOE s are below 10,000 for AFB 1 and also for AFM 1 where some surveys, particularly for the younger age groups, have an MOE below 10,000. This raises a health concern. The estimated cancer risks in humans following exposure to AFB 1 and AFM 1 are in‐line with the conclusion drawn from the MOE s. The conclusions also apply to the combined exposure to all five aflatoxins.

Monday, August 10, 2020

Evidence and Ethics in Food Fortification Policy Development

The primary objective of food fortification policy and programs is generally the “protection of public health and safety”. The ‘protection’ indicates the benefits associated with mandatory food fortification. On the other hand, ‘public health and safety’ refers to the risk of harm resulting from excessive nutrient intake. These two dimensions create ambiguity for the decision makers. The exposure to the raised level of nutrients can also have ethical consequences. The decision on fortification policy should be based both on the evidence and ethics.

The food fortification policy must be informed by sound scientific evidence. We generally use a term: evidence-informed-policy-making decision. There should be two types of evidence: evidence of food fortification to ‘promote’ public health; and evidence to ‘protect’ public health.

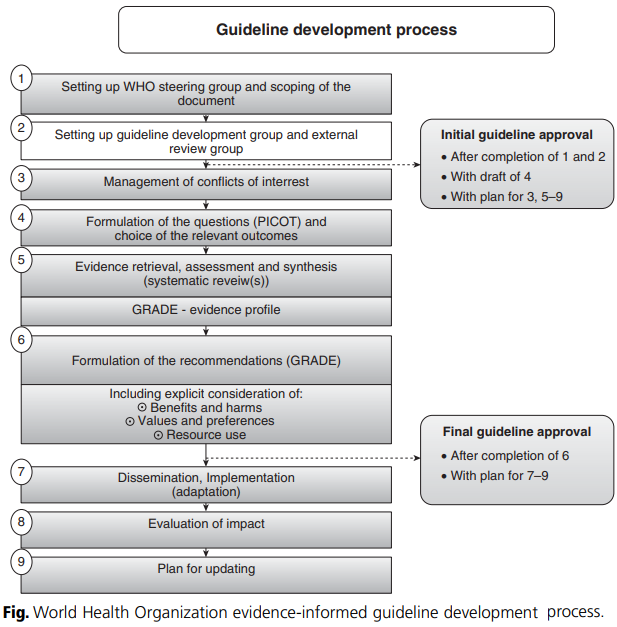

The evidence hierarchy method is used to evaluate the quality of evidence. For example, evidence based on randomized controlled trials (RCTs) is considered high quality. The process for developing evidence-informed guidelines was developed by WHO (2009). It consists of a nine step procedure as shown in figure below.

Friday, August 7, 2020

Thursday, August 6, 2020

Comparison of Aflatoxin B1 contamination in different categories of food products

Monday, August 3, 2020

तोरी र रेपसिडको तेलमा भटमासको तेलको मिसावट सम्बन्धि प्रकाशित लेख

प्रकाशित लेखको लिंक यस प्रकार रहको छ l

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2013.11.030

लेखको पूर्ण पाठ यस प्रकार रहको छ l

Sunday, August 2, 2020

Nepal Burden of Disease 2017

I have just found the "Nepal Burden of Disease 2017" study report. One of the graph presented in the report is shown below. The graph shows that "low whole grains", "low fruits", "low nuts and seed" each contributes around 5% of the total death. What's your opinion on the report?

The Executive Summary from the report is as follows:

"The Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study is a systematic effort to quantify the comparative magnitude of health loss due to diseases, injuries, and risk factors by age, sex, and geographies for specific points in time. It provides a comprehensive picture of total health loss due to diseases, injuries, and death. IHME has recently produced GBD 2017 estimates, which highlight Nepal’s health performance in terms of mortality, morbidity, and overall disease burden. These have been extracted to produce this Nepal Burden of Disease (NBoD) Study 2017 Report.

The GBD, and thus the NBoD (Nepal Burden of Disease) Study 2017, measures overall mortality, causes of mortality, causes of morbidity, and risk factors. Overall mortality is expressed in the form of number of deaths due to diseases and injuries and their rates per 100,000 populations. Causes of mortality are captured through years of life lost (YLLs), which give years of life lost due to premature death from a disease or injury. Years lived with disability (YLDs) measure causes of morbidity; they are used to indicate the number of years lived with disability due to a nonfatal disease or injury. YLLs and YLDs together give the overall burden of disease or injury. It is expressed in the form of disability adjusted life years (DALYs). Results described in the NBoD 2017 report reveal that females are expected to live longer (73.3 years) than males (68.7 years). Life expectancy increased from 59 to 73 years for females, and 58 to 69 years for males, between 1990 and 2017. However, not all these additional years gained will be healthy ones. Females are expected to live 62 years of healthy life, while males will live 60 years of healthy life. This discrepancy between life expectancy and healthy life expectancy is due to years of healthy life lost as a result of ill health and disability.

A total of 182,751 deaths are estimated in Nepal for the year 2017. Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) are the leading causes of death – two thirds (66%) of deaths are due to NCDs, with an additional 9% due to injuries. The remaining 25% are due to communicable, maternal, neonatal, and nutritional (CMNN) diseases. Ischemic heart disease (16.4% of total deaths), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (9.8% of total deaths), diarrheal diseases (5.6% of total deaths), lower respiratory infections (5.1% of total deaths), and intracerebral hemorrhage (3.8% of total deaths), were the top five causes of death in 2017. The rise of NCDs is partly due to the changing age structure and lifestyle changes such as increasing sedentary behavior, tobacco use, changes in eating habits, and harmful use of alcohol. Similarly, out of the total (5,850,044) YLLs due to premature death (people dying earlier than their potential life expectancy), 49% are due to NCDs, 39% due to CMNN diseases and the remaining 12% due to injuries. The top five causes (all ages both sexes) of YLLs are ischemic heart disease (11.3% of total YLLs), lower respiratory infections (7.9% of total YLLs), neonatal encephalopathy (5.7% of total YLLs), COPD (5.5% of total YLLs), and diarrheal diseases (4.5% of total YLLs). The leading causes of morbidity (YLDs) are low back pain, migraine, COPD, and other musculoskeletal disorders. Approximately 59% of disease burden (including premature death and disability -DALYs) in 2017 is due to NCDs, 31% due to CMNN diseases, and 10% due to injuries. Ischemic heart disease (7.6% of DALYs), COPD (5.4% of DALYs), and lower respiratory infections (5.2% of DALYs) are the top three disease conditions causing most of the disease burden in 2017. The findings further reveal that short gestation for birth weight (7.5% of total DALYs), high systolic blood pressure (6.7% of total DALYs), smoking (6.5% of total DALYs), high blood glucose level (5.5% of total DALYs), and low birth weight for gestation (4.7% of total DALYs) are the top five risk factors driving death and disability in Nepal. From the results presented in the NBoD 2017 report, NCDs are increasingly becoming a major public health issue. Notably, ischemic heart disease and COPD are top causes contributing significantly to the burden of disease (BoD). Maternal and child health outcomes are improving but should not be neglected as there is still much progress to be made. Notable risk factors are metabolic risk factors, ambient and household air pollution, and finally, behavioural risk factors such as smoking. The national BoD profile in 2017 looks vastly different from 1990, or even 2007: these changes must be reviewed and addressed, and Nepal’s health policy priorities, strategies, and resource allocations must adapt accordingly."

Thursday, July 30, 2020

Wednesday, July 29, 2020

Excess iodine intake and its relation with thyroid dysfunction

For the control of Iodine Deficiency Disorder (IDD), Universal salt Iodization (USI) was implemented. As a result of it, Nepal is heading towards iodine sufficiency however the prevalence of clinical and sub-clinical hypothyroidism is still higher.The increased prevalence of thyroid disorders can be result of iodine deficiency or excess of iodine intake. The prevalence of excess iodine intake is hiking all over the world including Nepal. A study done in 1000 patients (with 270 clinical hypothyroidism patients) showed anti-TPO (Thyroid Peroxidase) antibody positive. The study also stated that the cause of hypothyroidism in present day Nepal was chronic autoimmune thyroiditis (Hashimoto's thyroiditis). As stated earlier, the status of iodine consumption in Nepal is moving from iodine deficiency to adequate or excess, there might be higher burden of thyroid disorders in Nepal due to the increased prevalence of autoimmune thyroiditis (Pokharel, S., 2019).

A community based cross sectional study done in Udaypur (Nepal) in primary school aged children (6 years to 12 years) showed 10% (n=20) prevalence of thyroid dysfunction (sub-clinical hypothyroidism). Majority of the participants were reported to have excess urinary iodine concentration (UIC). The sensitive marker of recent dietary iodine intake is Urinary iodine rather than thyroid dysfunction. The analysis of thyroid hormones showed 1.6% of school age children had sub-clinical hyperthyroidism.

Saturday, July 18, 2020

फलफुलको रसको प्रस्तावित गुणस्तर

Friday, July 17, 2020

Federal Inspections and Law Enforcement Tools used by FDA (US Food Regulation series: Part 5)

We have been publishing a series of posts related to US Food Regulation. We have already completed four parts of the series. The first part of the series entitled “US Food Law and Regulation Series: Part 1” was focused on the discussion of different regulatory body such as FDA, USDA/FSIS, CDC, NMFS, EPA, DHS etc. “US Food Law and Regulation Series: Part 2” described the issues related to food, dietary supplement and drug. The third part was about the "History of the regulation of dietary supplements (US Food Regulation series: Part 3). In the fourth part, we discussed on the topic of "Jurisdictional overlap between FDA and USDA (US Food Regulation series: Part 4)".

In this post we will discuss about the "Federal Inspections and Law Enforcement Tools used by FDA".

Generally, FDA does not go to the facility for inspection on a daily basis. FDA conducts warrantless inspections generally for a special cause such as recall, adverse events, or for surveillance inspection. The regulatory work can be divided into two groups: “pre-market” and “post-market surveillance” activities.

Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition (CFSAN) of FDA is mainly responsible for pre market activities of food products. In addition, Center for Veterinary Medicine (CVM), Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER), Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER), Center for Device and Radiological Health (CDRH), and Center for Tobacco Products (CBT) are also product-oriented centers of FDA focusing on pre-market surveillance activities.

The post market surveillance activities are mainly the responsibility of Office of Regulatory Affairs (ORA). It works for all the six product-oriented centers and not only for CFSAN. Hence, it carries out investigation of drug, medical device, cosmetic, biologics, veterinary products, food, beverage, and dietary supplements. The criminal investigation part of FDA is handled by Office of Criminal Investigations (OCI).

FDA enforcement tools

FDA uses different law enforcement tools as per Food, Drug and Cosmetic act. The most important tools are as follows:

It is simply a notice of potential violations found during inspection and is issued by the inspector after facility inspection . It only contains opinion of inspectors and is not reviewed by a compliance office or other FDA officers prior to being issued.

b) Warning letters as enforcement instruments

The first enforcement tool used by FDA is a warning letter, which functions as a prior notice. This is not a statutory creature and is not mandatory. FDA can initiate formal enforcement action without warning letters.

The Form 483 and warning letters are informal enforcement actions of FDA. There are five formal enforcement actions taken by FDA: (1) seizures and administrative detentions, (2) recalls, (3) import refusals and alerts, (4) restraining order or injunctions, and (5) suspension of facility registration.

The decision of seizure by FDA is taken only when there is a question of safety. Seizure requires court warrant and is carried out by US Marshals. FDA is only involved indirectly. An administrative detention is less severe form of temporary action. After FSMA regulation, if FDA agents have “reason to believe food is adulterated or misbranded”, they can take temporary hold of products for 30 days to carry out investigation.

2) Recalls

Recall is one of the best known FDA enforcement actions. Recall is mainly linked with some type of outbreak of food-borne illness. Generally, recall is a voluntary action carried out by the manufacturer. After the enforcement of Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA), FDA is authorized to force a recall without court order under certain circumstances.

3) Import Refusal and Import Alerts

Before entering the US market, products must pass through both the customs and FDA. Previously, FDA agent used to randomly inspect the containers based on their experience or previous history. Now, FDA has launched PREDICT (Predictive Risk-based Evaluation for Dynamic Import Compliance Targeting) system which uses a complex algorithm to determine the risk and the likelihood of violation on a particular product. The new system is an example of Risk based food import control system.

The legislation states that FDA can refuse entry to a products based on the examination of samples that appears adulterated or misbranded. FDA may also issue an import alert that essentially acts as a blacklist. If a facility is on an import alert, all the shipments can be refused (detention without physical examination (DWPE)). The petition-for-removal from import alert takes a long process (may be more than a year) and must present evidence on how the violation was corrected. FSMA regulation has mandated a new rule known as Foreign Supplier Verification Program (FSVP).

Tuesday, July 14, 2020

Jurisdictional overlap between FDA and USDA (US Food Regulation series: Part 4)

In general, USDA through FSIS is responsible for regulating meat, poultry and egg products. However, there are areas of overlaps and confusion. Let’s take some examples:

1. A sausage product is regulated by both the FDA and USDA. The meat filling is regulated by USDA and the casing containing meat of no nutritional value is regulated by FDA.

2. The shelled eggs, chicken feed and egg labeling is regulated by FDA, while the egg products (liquid, dehydrated, frozen etc), the laying facilities, grading of eggs are regulated by USDA.

We can imagine the level of confusion it can create. A single food safety agency can provide a more cohesive approach. Facilities regulated by both the agencies are having difficulties fulfilling the requirements. For example, a chicken tomato soup making facility will be inspected by both the agencies. It creates confusion and overlapping of authorities during inspection, enforcement actions and carrying out the compliance programs.

Let’s try to compare the FDA and USDA jurisdiction in the following table.

|

FDA jurisdiction |

USDA jurisdiction |

|

All non-specified red meats (bison, rabbits, game animals, zoo animals and all members of the deer family including elk (wapiti) and moose)), all non-specified birds including wild turkeys, wild ducks, and wild geese |

Cattle, sheep, swine, goats, horses, mules or other equines, including their carcasses and parts, turkeys, ducks, geese and guineas, domesticated chicken, turkey, duck, goose or guinea. |

|

Products with 3 % or less raw meat; less than 2% cooked meat or other portions of the carcass; or less than 30 % fat, tallow or meat extract, alone or in combination |

Products containing greater than 3% raw meat; 2% or more cooked meat or other portions of the carcass; or 30% or more fat, tallow or meat extract, alone or in combination |

|

Products containing less than 2% cooked poultry meat; less than 10% cooked poultry skins, giblets, fat and poultry meat (limited to less than 2%) in any combination |

Products containing 2% or more cooked poultry; more than 10% cooked poultry skins, giblets, fat and poultry meat in any combination |

|

Closed-face sandwiches |

Open-face sandwiches |

|

Shell eggs and egg containing products that do not meet USDA’s definition of “egg product.” |

Dried, frozen, or liquid eggs, with or without added ingredients, but has many exceptions. The following products, among others, are exempted as not being egg products: freeze-dried products, imitation egg products, egg substitutes, dietary foods, dried no-bake custard mixes, egg nog mixes, acidic dressings, noodles, milk and egg dip, cake mixes, French toast, sandwiches containing eggs or egg products, balut and other similar ethnic delicacies. Products that do not fall under the definition, such as egg substitutes and cooked products, are under FDA jurisdiction |

|

Egg processing plants (egg washing, sorting, packing) |

Egg products processing plants (egg breaking and pasteurizing operations) |

|

Cheese pizza, onion and mushroom pizza, meat flavored spaghetti sauce (less than 3 % red meat), meat flavored spaghetti sauce with mushrooms, (2% meat), pork and beans, sliced egg sandwich (closed-face), frozen fish dinner, rabbit stew, shrimp-flavored instant noodles, venison jerky, buffalo burgers, alligator nuggets, noodle soup chicken flavor |

Pepperoni pizza, meat-lovers stuffed crust pizza, meat sauces (3% red meat or more), spaghetti sauce with meat balls, open-faced roast beef sandwich, hot dogs, corn dogs, beef/vegetable pot pie, Chicken sandwich (open face), chicken noodle soup |

Monday, July 13, 2020

Is it time to revisit the standard of "Iodised salt"?

WHO International Health Regulations Capacity Assessment

Thursday, July 9, 2020

History of the regulation of dietary supplements (US Food Regulation series: Part 3)

This is the third part of the series. In this post, we will shortly discuss the EU and Japanese system of regulation of dietary supplement. However, our main focus will be the regulatory mechanism of dietary supplement in USA. The history of FDA with dietary supplement is the learning for the entire world. The issues and challenges faced by FDA, court decisions, background and the driving force for the development of a separate dietary supplement regulation will be discussed chronologically.

Let’s start with EU and Japanese system.

European Food Safety Authority uses a term food supplements. European Union (EU) has analogous regulatory system compared to US. The main dietary regulation is found in 2002 EU directive, Directive 2002/46/EC. It has a list of permitted vitamin and mineral components for specific intended uses. The regulation 1924/2006 related to nutrition and health claims was adopted in 2006 and it demands the verification for substantiation and approval for the claims.

In Japan, all the supplements are treated as food. Yet it offers the most restrictive regulation of dietary supplements. Supplements are categorized into 4 categories: Food for special dietary uses; Food for specified health uses; Health foods; and Health foods with nutrient function claims. The structure/function claims are not allowed and only the few health claims are allowed in certain supplements.

The details of the discussion on EU and Japanese regulatory systems have been skipped for the moment to focus our discussion on history of regulation of dietary supplement in USA.

Regulation of dietary supplement by US FDA

Let's start our discussion chronologically starting form the beginning of 19th century.

In the past, only a small number of ingredients (usually common food constituents) were used as supplement. Cod liver oil having vitamins A and D is probably the first dietary supplement in USA. The 1906 Act provided the first distinction between food and drug, however the regulation of both products were identical. The classification was mainly based on active molecules and the packaging claim.

With increasing public interest in vitamin supplements, FDA started working in the vitamin claims and established a Vitamin Division in 1935. It also started working on new ingredients/ compounds with claimed health benefits. FDA filed a criminal case against a vitamin product containing milk, sugar, wheat starch and vitamins with health claims of curing high blood pressure, low blood pressure, dropsy, toxic goiter, and heart disease. It was probably the first attempt to take legal action against the vitamin product with disease claims in USA. The FDA experience with such case did influence and shape the upcoming regulation in the field of dietary supplement. The 1938 act provided authority to FDA for the regulation of supplement type products having labeling of “food for special dietary uses” under the misbranding provisions. Three groups of foods were initially focused in the regulation under the 1938 act: (1) “staple foods fortified with vitamins and minerals” were regulated with standards of identities, limits on the amount of nutritional ingredients and barring any health claims; (2) “foods for special dietary uses” (e.g. infant foods and foods for diabetics ); (3) dietary supplements were regulated either as conventional food or food for special dietary purposes. In the early days, parenteral supplements, despite not having labeling of disease claims, were exclusively regulated as drugs. Nevertheless, the products with an intended use to supplement the daily diet were regulated as foods.

This approach didn’t work well to regulate claims on vitamins, minerals and dietary supplements, as regulations for special dietary food was not designed in that way. In a series of court case between FDA and different manufacturers (such as Nutrilite, Abbott, Dextra, Vitasafe, Nutrilab) the concept and classification of dietary supplement emerged. Among them the most significant case was the one that of Nutrilab. The court decided that “intended use” could be the greatest tool to classify supplements. FDA was allowed to classify the product with alleged disease claims or medicinal use as drugs, and should pass through premarket clearance. On the other hand, FDA should regulate the dietary supplements without claims or with nutritional claims as food.

FDA attempted to issue a separate regulation for dietary supplements in 1962 with a set dosage levels of supplements. FDA proposed to permit a single nutrient dietary supplement with levels close to US Recommended Daily Allowance (RDA), while limiting the number of multivitamin and mineral products. The proposed regulation was to classify the “high potency” dietary supplements as drug, which created a series of spark and outcry. FDA eventually needed to drop its proposal. Afterwards, Congress attempted to regulate vitamins and minerals with therapeutic claims using “Vitamin and Mineral Amendment of 1976”. This was the first specific attempt to address dietary supplements by stopping the FDA to regulate threshold based “high potency” dietary supplement as drug. However, the scope of the legislation was narrow for regulating different dietary supplement products. FDA continued its attempt to regulate number of supplements using drug regulations.

In 1990, nutrient content and other claims for food were established in Nutritional Labeling and Education Act (NELA). It established the concept of nutritional labeling. NELA made it mandatory to declare any vitamin and mineral supplementation in the label. It also opened the door for health claims for dietary supplements to make certain claims about the benefits of nutrients it contained. It allowed the established claims related to the reduced risk of disease or health conditions. However, a general dietary guidance (such as fruits and vegetables as part of healthy diet) is not considered a health claim. FDA was authorized to review and approve the health claims using the criteria set by NLEA. FDA needed to conduct an exhaustive review of scientific literatures to obtain “significant scientific agreement” on the health claims. Only the FDA approved health claims were allowed.

The history of L-tryptophan regulation by FDA should be remembered here. FDA was concerned with an supplement ingredient L-tryptophan (an amino acid) over the adverse health effect of eosinophilla myalgia syndrome. FDA issued a consumer advisory warning to the public about that supplement and established a task force to examine. That task force recommended the FDA to regulate that supplement as drug, without considering the possibility of health claims under NELA. It was ultimately considered an aggressive enforcement approach of FDA by different experts and law makers.

The era of confusion on the regulation of dietary supplements ranged from 1906 till 1994. A rapidly growing market with unscrupulous claims of dietary supplements was an increasing challenge for FDA. Even judiciary struggled to develop consistent interpretation of the act in the field of dietary supplements. It ultimately demanded for the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act (DSHEA) of 1994. Congress passed DSHEA to restrict FDA ability to impose unnecessary control on dietary supplements, because of unrealistic and aggressive enforcement of FDA in the case of L-tryptophan case. Enactment of DSHEA was a ground breaking step in the regulation of dietary supplement. It established a framework for new Good Manufacturing Practices (GMPs) for the dietary supplement industries.

Tuesday, July 7, 2020

US Food Law and Regulation Series: Part 2

In this post, we will try to discuss on the FDA jurisdiction and authority.

The FDA is responsible for protecting and promoting public health through the control and supervision of food safety, tobacco products, dietary supplements, prescription and over-the-counter pharmaceutical drugs (medications), vaccines, biopharmaceuticals, blood transfusions, medical devices, electromagnetic radiation emitting devices (ERED), cosmetics, animal foods & feed and veterinary products.

In general, there are 4 categories of products regulated by US FDA: food & dietary supplement, cosmetic, drug and device. The fifth category is those not regulated by FDA. This classification is the heart of all the enforcement decision. Hence, let’s try to discuss and understand this classification better in both technical and legal terms.

The legal definition of food, food additive, dietary supplement and drug are as follows:

------------------------------- you can skip these legal definition, if you are not interested ----------------

"Section 201 (f) “food”: “food” means (1) articles used for food or drink for man or other animals, (2) chewing gum, and (3) articles used for components of any such article"

"Section 201(s) “food additive”: “food additive” means any substance the intended use of which results or may reasonably be expected to result, directly or indirectly, in its becoming a component or otherwise affecting the characteristics of any food (including any substance intended for use in producing, manufacturing, packing, processing, preparing, treating, packaging, transporting, or holding food; and including any source of radiation intended for any such use), if such substance is not generally recognized, among experts qualified by scientific training and experience to evaluate its safety, as having been adequately shown through scientific procedures (or, in the case of a substance used in food prior to January 1, 1958, through either scientific procedures or experience based on common use in food) to be safe under the conditions of its intended use; except that such term does not include—(1) a pesticide chemical residue in or on a raw agricultural commodity or processed food; or(2) a pesticide chemical; or(3) a color additive; or(4) any substance used in accordance with a sanction or approval granted prior to the enactment of this paragraph 4 pursuant to this Act [enacted Sept. 6, 1958], the Poultry Products Inspection Act (21 U.S.C. 451 and the following) or the Meat Inspection Act of March 4, 1907 (34 Stat. 1260), as amended and extended (21 U.S.C. 71 and the following);(5) a new animal drug; or(6) an ingredient described in paragraph (ff) in, or intended for use in, a dietary supplement"

"Section 201 (ff) “Dietary Supplement”: “dietary supplement”—(1) means a product (other than tobacco) intended to supplement the diet that bears or contains one or more of the following dietary ingredients:(A) a vitamin;(B) a mineral;(C) an herb or other botanical;(D) an amino acid;(E) a dietary substance for use by man to supplement the diet by increasing the total dietary intake; or(F) a concentrate, metabolite, constituent, extract, or combination of any ingredient described in clause (A), (B), (C), (D), or (E);(2) means a product that—(A) (i) is intended for ingestion in a form described in section 411(c)(1)(B)(i); or(ii) complies with section 411(c)(1)(B)(ii);(B) is not represented for use as a conventional food or as a sole item of a meal or the diet; and(C) is labeled as a dietary supplement; and(3) does—(A) include an article that is approved as a new drug under section 505 or licensed as a biologic under section 351 of the Public Health Service Act (42 U.S.C. 262) and was, prior to such approval, certification, or license, marketed as a dietary supplement or as a food unless the Secretary has issued a regulation, after notice and comment, finding that the article, when used as or in a dietary supplement under the conditions of use and dosages set forth in the labeling for such dietary supplement, is unlawful under section 402(f); and(B) not include—(i) an article that is approved as a new drug under section 505, certified as an antibiotic under section 507 7, or licensed as a biologic under section 351 of the Public Health Service Act (42 U.S.C. 262), or(ii) an article authorized for investigation as a new drug, antibiotic, or biological for which substantial clinical investigations have been instituted and for which the existence of such investigations has been made public, which was not before such approval, certification, licensing, or authorization marketed as a dietary supplement or as a food unless the Secretary, in the Secretary’s discretion, has issued a regulation, after notice and comment, finding that the article would be lawful under this ActExcept for purposes of section 201(g), a dietary supplement shall be deemed to be a food within the meaning of this Act"

"Section 201(g) (1)(c) : the term ‘drug’ means … (B) articles intended for use in the diagnosis, cure, mitigation, treatment, or prevention of disease in man or other animals…(C) articles (other than food) intended to affect the structure or any function of the body of man or other animals.” Also called the “food exception,” it is the most cited defense to a drug classification of a food-based product claiming some drug-like effect."

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

There were multiple incidences of ambiguity in the classification of product as food, food supplement and drug. There were multiple disputes between FDA and manufacturer in the product classification and for deciding the regulatory requirements. Such issues were challenged in the US court.

This confusion and ambiguity exists even in US where a single Food and Drug Administration (FDA) exist. In number of cases, the federal court reached a conclusion that the definitions are overlapping and the determination of classification of product only based on definition is very difficult without taking into account the “intended use” concept. It means, if a product is making "drug-like claims (such as prevention or cure of disease)" on labeling, we can slide the classification from food towards drug, while with "nutrition and health claims within the domain of food" can be considered as a food product. For example, honey can appropriately be classified as food, as it is often eaten plain or added as a sweetener to other foods. However, if the label states therapeutic/ disease claims (prevention or treatment of disease) such as “calming an upset stomach”, it falls under the drug definition of section 201(g)(1)(c)(B). On other hand, if the label states “nutrition claims or structure-function claim” such as “honey slows the absorption of trans fats”, it is considered in the food category. Therefore, a food supplement with nutrition and health claims cannot be classified in a drug category, however, those having drug-like claims (such as prevention or cure of disease) will clearly fall in the drug category for regulation. The court also mentioned that no product normally used as a food can be classified as a drug. Classification is the most critical issue as it determines the appropriate regulatory burden in the product as shown in the figure. The regulatory requirement for drug and medical device is significantly more burdensome than for other classes of products.

Monday, July 6, 2020

US Food Law and Regulation Series: Part 1

Let me start with federalism and the structure of US Government. The USA is a union of several sovereign States defined in the US Constitution. The framework for federal regulation, interstate commerce, individual and corporate freedoms and liberties etc are defined in the constitution. It establishes specific powers to the federal government and the States, based on the concept of federalism.

The FDA is under the department of health and human services. FDA has following different divisions.

Department of Health and Human Services

· Food and Drug Administration

- Office of the Commissioner

- Office of Operations

- Office of Policy, Planning, Legislation, and Analysis

- Office of Medical Products and Tobacco

- Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER)

- Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH)

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER)

- Oncology Center of Excellence (OCE)

- Center for Tobacco Products (CTP)

- Office of Foods and Veterinary Medicine

- Center for Veterinary Medicine (CVM)

- Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition (CFSAN)

- Office of Global Regulatory Operations and Policy (GO)

- National Center for Toxicological Research (NCTR)

- Office of Regulatory Affairs

Organization structure concept described in National Food Safety Policy 2076

Sunday, July 5, 2020

Dietary Supplement issues in National Food Safety Policy of Nepal

Saturday, July 4, 2020

Vitamin and mineral requirements in human nutrition

Wednesday, July 1, 2020

WHO SEARO Framework for action on Food Safety

"Component 1: Policy and legal framework

1. Develop, review and regularly update food safety policies, legislations and standards to include all requirements of a risk-based food control system, to address current emerging

issues, and to harmonize food legislations across various competent authorities in line with international requirements such as Codex Alimentarius Commission, the World Trade Organization the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE), Sanitary and Phytosanitary (WTO SPS) agreement and Technical Barriers to Trade (TBT) measures, where applicable.

2. Disseminate food safety policies, regulations and standards through various means, including online tools such as official websites.

Facilitate cross-sectoral coordination, integration of food control services and synergy in actions at the national and sub-national levels to achieve common food safety goals.

1. Develop and implement risk-based inspection across the food chain.

2. Allocate adequate resources for inspection including appropriate inspection tools and sampling plans.

3. Establish a monitoring programme for specific contaminants and residues.

4. Develop guidance documents and tools for food business operators (FBOs) to develop food safety management systems such as good hygienic practices (GHP), good manufacturing practices (GMP), hazards analysis and critical control points (HACCP), traceability, recall, labelling, and food fraud vulnerability assessment and mitigation plan, and encourage them to conduct self-audit programmes.

1. Establish a national integrated data management system (data collection, central database, quality monitoring), conduct structured and timely data analysis for risk assessment, set standards, prioritize and participate in regional and international data sharing, e.g. Codex, global environment monitoring system (GEMS-food database).

2. Encourage utilization of information for evidence-based policy advocacy and decision making.

3. Collect and share data on FBD outbreaks through national disease surveillance systems (EBS and IBS).

4. Develop platforms for collaboration with academicians and researchers in conducting scientific studies to support risk assessment on food safety, conduct specific research to test hypotheses generated from FBD surveillance, and provide and sustain continued education for professional development of food safety officials.

1. Establish or have access to adequate laboratory services, including reference laboratories and satellite/mobile laboratory units equipped with reliable rapid test kits for on-thespot testing.

2. Develop and implement a laboratory network at the national and sub-national levels, collaborate with regional reference laboratories to improve efficiency and cost– effectiveness.

3. Develop and implement a sample management system.

4. Ensure that internal and external quality control/assurance systems (proficiency testing) for food testing are in place, including accreditation, where necessary.

1. Develop, update and test cross-sectoral preparedness and response plans for food safety emergencies in line with the One Health approach and integrated with the NAPHS.

2. Use the INFOSAN community website/network to communicate on food safety incidents or emergencies and participate in identification/traceability/recall of implicated products.

3. Build or strengthen capacity to conduct investigation on FBD outbreaks and food safety events using the One Health approach.

1. Develop education and capacity-building programmes on food safety for professionals through various means, including online training.

2. Establish guidance documents for FBOs to manage food safety risks in line with national requirements.

3. Identify training needs and provide assistance/encouragement to FBOs to deliver continuous education and communication on food safety for all personnel involved in the food chain.

4. Provide food safety awareness and training for food handlers/street food vendors/ small-medium enterprises (SMEs) to improve hygiene and food safety practices.

5. Develop and implement consumer awareness programmes promoting food hygiene practices, food labelling, healthy diets, food allergy prevention, including the “Five keys for safer food” through various means such as online communication channels

(e.g. official websites and social media) as per country context and needs of the target population.

6. Review and update available food safety information regularly.

7. Design and provide tailored and specific food safety information targeting vulnerable populations (infants, pregnant and lactating mothers, the elderly and immunocompromised).

8. Develop appropriate mechanisms to monitor public concerns and social media information on food safety and response.

9. Develop media and FBO sensitization programmes on food safety.

10. Encourage incorporation of food safety-related lessons and activities in school. "

Tuesday, June 30, 2020

Compilation of nutrition and health claims evaluated by EFSA

Monday, June 29, 2020

Fish Oil Supplement

Sunday, June 28, 2020

EFSA evaluation of health claims related to COPPER

Claims

|

EFSA opinion

reference

|

Status

|

Copper contributes to maintenance of normal

connective tissues

|

2009;7(9):1211

|

Authorised

|

Copper contributes to normal

energy-yielding metabolism

|

2009;7(9):1211

2011;9(4):2079

|

Authorised

|

Copper contributes to normal functioning of

the nervous system

|

2009;7(9):1211

2011;9(4):2079

|

Authorised

|

Copper contributes to normal hair

pigmentation

|

2009;7(9):1211

|

Authorised

|

Copper contributes to normal iron transport

in the body

|

2009;7(9):1211

|

Authorised

|

Copper contributes to normal skin

pigmentation

|

2009;7(9):1211

|

Authorised

|

Copper contributes to the normal function

of the immune system

|

2009;7(9):1211

2011;9(4):2079

|

Authorised

|

Copper contributes to the protection of

cells from oxidative stress

|

2009;7(9):1211

|

Authorised

|

Copper contributes to the cholesterol and

glucose

|

2009;7(9):1211

|

Non-authorised

|

Popular Posts

-

“On the occasion of upcoming World Food Safety Day on 7 th June 2020 ” The world is facing the threats of COVID-19 pande...

-

This book delves into the complex and dynamic nature of different food products, offering a comprehensive estimation of macronutrients, mi...

-

With the advancement of analytical capabilities, new chemical contaminants having no regulatory limits are being detected in the foods. U...

-

ट्रान्स फ्याटलाई अति खराब चिल्लो (अखचि) भनि नेपाली नामकरण गर्ने बारे छलफल भएको सुनिन्छ, त्यसमा सहमत हुनेहरु पनि छन्, र असहमति जनाउनेहरु पनि...

-

In the previous posts, we had evaluated the National Food Control System of Nepal using the tool developed by FAO/WHO . The evaluation w...

-

Turmeric is one of the most common household spices in Asian kitchen. It contains a yellow colored antioxidant called curcumin. It ...