Food Science and Technology, Nutrition, Food Safety, Dietary Supplement & Health related blog - Kshitij Shrestha

Friday, August 28, 2020

Risk Assessment of Aflatoxins from JECFA

Thursday, August 13, 2020

EFSA Risk Assessment of Aflatoxins in food

Abstract

EFSA was asked to deliver a scientific opinion on the risks to public health related to the presence of aflatoxins in food. The risk assessment was confined to aflatoxin B1 (AFB 1), AFB 2, AFG 1, AFG 2 and AFM 1. More than 200,000 analytical results on the occurrence of aflatoxins were used in the evaluation. Grains and grain‐based products made the largest contribution to the mean chronic dietary exposure to AFB 1 in all age classes, while ‘liquid milk’ and ‘fermented milk products’ were the main contributors to the AFM 1 mean exposure. Aflatoxins are genotoxic and AFB 1 can cause hepatocellular carcinomas (HCC s) in humans. The CONTAM Panel selected a benchmark dose lower confidence limit (BMDL ) for a benchmark response of 10% of 0.4 μg/kg body weight (bw) per day for the incidence of HCC in male rats following AFB 1 exposure to be used in a margin of exposure (MOE ) approach. The calculation of a BMDL from the human data was not appropriate; instead, the cancer potencies estimated by the Joint FAO /WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives in 2016 were used. For AFM 1, a potency factor of 0.1 relative to AFB 1 was used. For AFG 1, AFB 2 and AFG 2, the in vivo data are not sufficient to derive potency factors and equal potency to AFB 1 was assumed as in previous assessments. MOE values for AFB 1 exposure ranged from 5,000 to 29 and for AFM 1 from 100,000 to 508. The calculated MOE s are below 10,000 for AFB 1 and also for AFM 1 where some surveys, particularly for the younger age groups, have an MOE below 10,000. This raises a health concern. The estimated cancer risks in humans following exposure to AFB 1 and AFM 1 are in‐line with the conclusion drawn from the MOE s. The conclusions also apply to the combined exposure to all five aflatoxins.

Monday, August 10, 2020

Evidence and Ethics in Food Fortification Policy Development

The primary objective of food fortification policy and programs is generally the “protection of public health and safety”. The ‘protection’ indicates the benefits associated with mandatory food fortification. On the other hand, ‘public health and safety’ refers to the risk of harm resulting from excessive nutrient intake. These two dimensions create ambiguity for the decision makers. The exposure to the raised level of nutrients can also have ethical consequences. The decision on fortification policy should be based both on the evidence and ethics.

The food fortification policy must be informed by sound scientific evidence. We generally use a term: evidence-informed-policy-making decision. There should be two types of evidence: evidence of food fortification to ‘promote’ public health; and evidence to ‘protect’ public health.

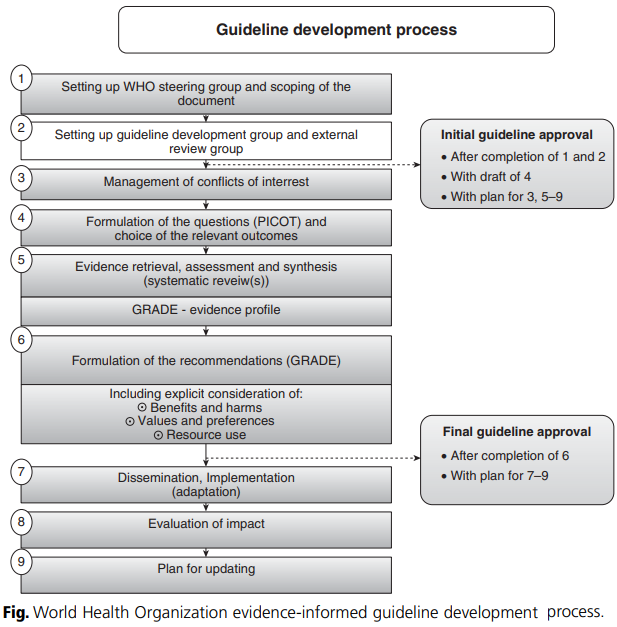

The evidence hierarchy method is used to evaluate the quality of evidence. For example, evidence based on randomized controlled trials (RCTs) is considered high quality. The process for developing evidence-informed guidelines was developed by WHO (2009). It consists of a nine step procedure as shown in figure below.

Friday, August 7, 2020

Thursday, August 6, 2020

Comparison of Aflatoxin B1 contamination in different categories of food products

Monday, August 3, 2020

तोरी र रेपसिडको तेलमा भटमासको तेलको मिसावट सम्बन्धि प्रकाशित लेख

प्रकाशित लेखको लिंक यस प्रकार रहको छ l

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2013.11.030

लेखको पूर्ण पाठ यस प्रकार रहको छ l

Sunday, August 2, 2020

Nepal Burden of Disease 2017

I have just found the "Nepal Burden of Disease 2017" study report. One of the graph presented in the report is shown below. The graph shows that "low whole grains", "low fruits", "low nuts and seed" each contributes around 5% of the total death. What's your opinion on the report?

The Executive Summary from the report is as follows:

"The Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study is a systematic effort to quantify the comparative magnitude of health loss due to diseases, injuries, and risk factors by age, sex, and geographies for specific points in time. It provides a comprehensive picture of total health loss due to diseases, injuries, and death. IHME has recently produced GBD 2017 estimates, which highlight Nepal’s health performance in terms of mortality, morbidity, and overall disease burden. These have been extracted to produce this Nepal Burden of Disease (NBoD) Study 2017 Report.

The GBD, and thus the NBoD (Nepal Burden of Disease) Study 2017, measures overall mortality, causes of mortality, causes of morbidity, and risk factors. Overall mortality is expressed in the form of number of deaths due to diseases and injuries and their rates per 100,000 populations. Causes of mortality are captured through years of life lost (YLLs), which give years of life lost due to premature death from a disease or injury. Years lived with disability (YLDs) measure causes of morbidity; they are used to indicate the number of years lived with disability due to a nonfatal disease or injury. YLLs and YLDs together give the overall burden of disease or injury. It is expressed in the form of disability adjusted life years (DALYs). Results described in the NBoD 2017 report reveal that females are expected to live longer (73.3 years) than males (68.7 years). Life expectancy increased from 59 to 73 years for females, and 58 to 69 years for males, between 1990 and 2017. However, not all these additional years gained will be healthy ones. Females are expected to live 62 years of healthy life, while males will live 60 years of healthy life. This discrepancy between life expectancy and healthy life expectancy is due to years of healthy life lost as a result of ill health and disability.

A total of 182,751 deaths are estimated in Nepal for the year 2017. Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) are the leading causes of death – two thirds (66%) of deaths are due to NCDs, with an additional 9% due to injuries. The remaining 25% are due to communicable, maternal, neonatal, and nutritional (CMNN) diseases. Ischemic heart disease (16.4% of total deaths), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (9.8% of total deaths), diarrheal diseases (5.6% of total deaths), lower respiratory infections (5.1% of total deaths), and intracerebral hemorrhage (3.8% of total deaths), were the top five causes of death in 2017. The rise of NCDs is partly due to the changing age structure and lifestyle changes such as increasing sedentary behavior, tobacco use, changes in eating habits, and harmful use of alcohol. Similarly, out of the total (5,850,044) YLLs due to premature death (people dying earlier than their potential life expectancy), 49% are due to NCDs, 39% due to CMNN diseases and the remaining 12% due to injuries. The top five causes (all ages both sexes) of YLLs are ischemic heart disease (11.3% of total YLLs), lower respiratory infections (7.9% of total YLLs), neonatal encephalopathy (5.7% of total YLLs), COPD (5.5% of total YLLs), and diarrheal diseases (4.5% of total YLLs). The leading causes of morbidity (YLDs) are low back pain, migraine, COPD, and other musculoskeletal disorders. Approximately 59% of disease burden (including premature death and disability -DALYs) in 2017 is due to NCDs, 31% due to CMNN diseases, and 10% due to injuries. Ischemic heart disease (7.6% of DALYs), COPD (5.4% of DALYs), and lower respiratory infections (5.2% of DALYs) are the top three disease conditions causing most of the disease burden in 2017. The findings further reveal that short gestation for birth weight (7.5% of total DALYs), high systolic blood pressure (6.7% of total DALYs), smoking (6.5% of total DALYs), high blood glucose level (5.5% of total DALYs), and low birth weight for gestation (4.7% of total DALYs) are the top five risk factors driving death and disability in Nepal. From the results presented in the NBoD 2017 report, NCDs are increasingly becoming a major public health issue. Notably, ischemic heart disease and COPD are top causes contributing significantly to the burden of disease (BoD). Maternal and child health outcomes are improving but should not be neglected as there is still much progress to be made. Notable risk factors are metabolic risk factors, ambient and household air pollution, and finally, behavioural risk factors such as smoking. The national BoD profile in 2017 looks vastly different from 1990, or even 2007: these changes must be reviewed and addressed, and Nepal’s health policy priorities, strategies, and resource allocations must adapt accordingly."

Popular Posts

-

“On the occasion of upcoming World Food Safety Day on 7 th June 2020 ” The world is facing the threats of COVID-19 pande...

-

This book delves into the complex and dynamic nature of different food products, offering a comprehensive estimation of macronutrients, mi...

-

With the advancement of analytical capabilities, new chemical contaminants having no regulatory limits are being detected in the foods. U...

-

ट्रान्स फ्याटलाई अति खराब चिल्लो (अखचि) भनि नेपाली नामकरण गर्ने बारे छलफल भएको सुनिन्छ, त्यसमा सहमत हुनेहरु पनि छन्, र असहमति जनाउनेहरु पनि...

-

In the previous posts, we had evaluated the National Food Control System of Nepal using the tool developed by FAO/WHO . The evaluation w...

-

Turmeric is one of the most common household spices in Asian kitchen. It contains a yellow colored antioxidant called curcumin. It ...